Odin is not only the god called upon in preparation for war, he is the god of poetry, the dead and magic as well. In a little known side gig, he was also petitioned by cadets at West Point to cancel parades with thunderstorms.

One fall day Plebe Year, my company, B-3, along with our entire regiment, was standing in formation in Central Area waiting for the start of yet another weekday afternoon parade. Central Area is out of view of the general public and where we lined up in preparation for parades. While the upperclassmen were more relaxed, we plebes stood there in full dress uniform, our tar buckets on our heads, and our M14 rifles extended at parade rest. The sky was dark with clouds and foretold the possible arrival of an impending storm. Somewhere in the distance, I heard a plaintive chant starting up, but I couldn’t make out what they were saying. Suddenly, it grew louder, closer and more distinct –

OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN…

One of our upperclassmen called out – “Beanheads! Take up the chant!!” (Beanhead was one of the less flattering terms the upperclassmen would call us Plebes)

What?!

“Beanheads!! Take up the call to ODIN. Let’s see if we can get this parade canceled!”

The thirty or so of us Plebes in B-3 quickly joined the cacophony.

OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN…

Soon, all 300 or so Plebes in the regiment were chanting. I have no idea what it sounded like to anyone in the bleachers on the parade ground itself, but they had to have heard us. We were LOUD and unrelenting. Always the same pace, always the same mournful sound, we continued…

OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN…

…

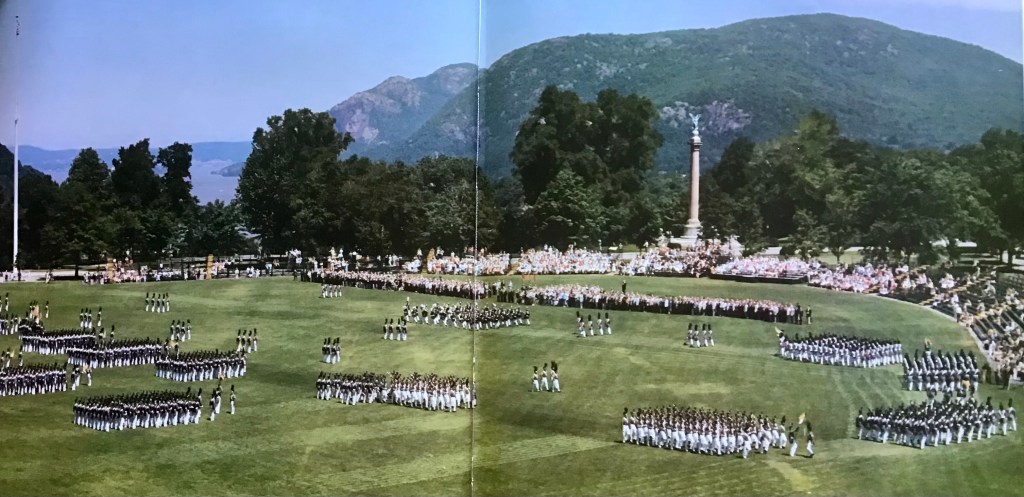

Parades… I never knew anyone at West Point, or in the military for that matter, who actually liked taking part in a parade. The public may enjoy watching them, but the participants? The cadets or soldiers who actually march in the parade? I don’t recall anyone ever saying to me “Wow Max, I am so looking forward to cleaning my weapon, dressing up in uniform, standing around in the hot sun (or freezing cold), and then marching in a review in front of the General. How about you?”

At West Point we did a lot of marching, and A LOT of parades, starting the day we arrived. The soundtrack of that first day was the drums from the Hellcats (West Point’s drum and bugle corps, made up of professional soldiers). They beat their drums all day long, as we learned to march and keep in step. That evening? We paraded to our swearing in ceremony, with parents, family, and the general public looking on.

Our last official parade took place the day before graduation in 1978.

In between those two events, we marched in an untold number of parades. Mondays through Thursdays, one of the four regiments would be in a parade for the public virtually every afternoon in the spring and fall. On Football Saturdays, there would be a double-regimental parade for every home game, and on Homecoming, the entire Corps of Cadets would perform in a parade. While we didn’t parade in the winter, the overall schedule resumed in the spring, and graduation provided another parade for the entire Corps. I learned to hate parades.

… In Central Area, our petition to Odin continued …

OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN…

A few raindrops started to fall. And then, a few more and it turned in to something between a sprinkle and a light shower. Our chant droned on.

OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN… OOOOOOOO-DIIIN…

I could see our commander conferring with the Battalion commander nearby. Suddenly, he returned. “COMPANY… ATTENNNSHUN!” We snapped to attention, the chanting stopped and there was silence, except for the sound of the rain hitting our hats and the ground. Would we march, or not?? Our Commander called out: “B-3 …DISMISSED!”

It worked! We all sprinted to our rooms, gaining an extra hour of rack time.

That evening as we assembled for dinner formation, our squad leader informed us that appealing to Odin to cancel a parade was an Old West Point tradition, and advised us to study up on him. He would quiz us later.

We learned Odin was the god of war in Germanic and Norse mythology. He was a protector of heroes, and fallen warriors joined him in Valhalla. In a bit of a juxtaposition, he was also the god of poets. He was associated with healing, death, royalty, knowledge, battle, victory, and sorcery. He gave up one of his eyes to gain wisdom. You will notice no where in that description is there any mention of rain, storms, or weather. Evidently, that skill was buried in history.

Over my remaining years at West Point, there were many times we appealed to Odin for rain to cancel a parade. The vast majority of the time, he ignored our pleas, and we emerged through the Sally Ports and onto The Plain for our parade before the Great American Public. They say the gods are fickle. Maybe that was the case with Odin.

As I was thinking about writing this blog a couple of months ago, 40-some years after that initial appeal to Odin, I was trading messages with a few classmates. We were discussing how infrequently parades were actually cancelled due to calling Odin, when Leroy Hurt said, “By the way, I finally found out why we chanted to Odin.” What!?

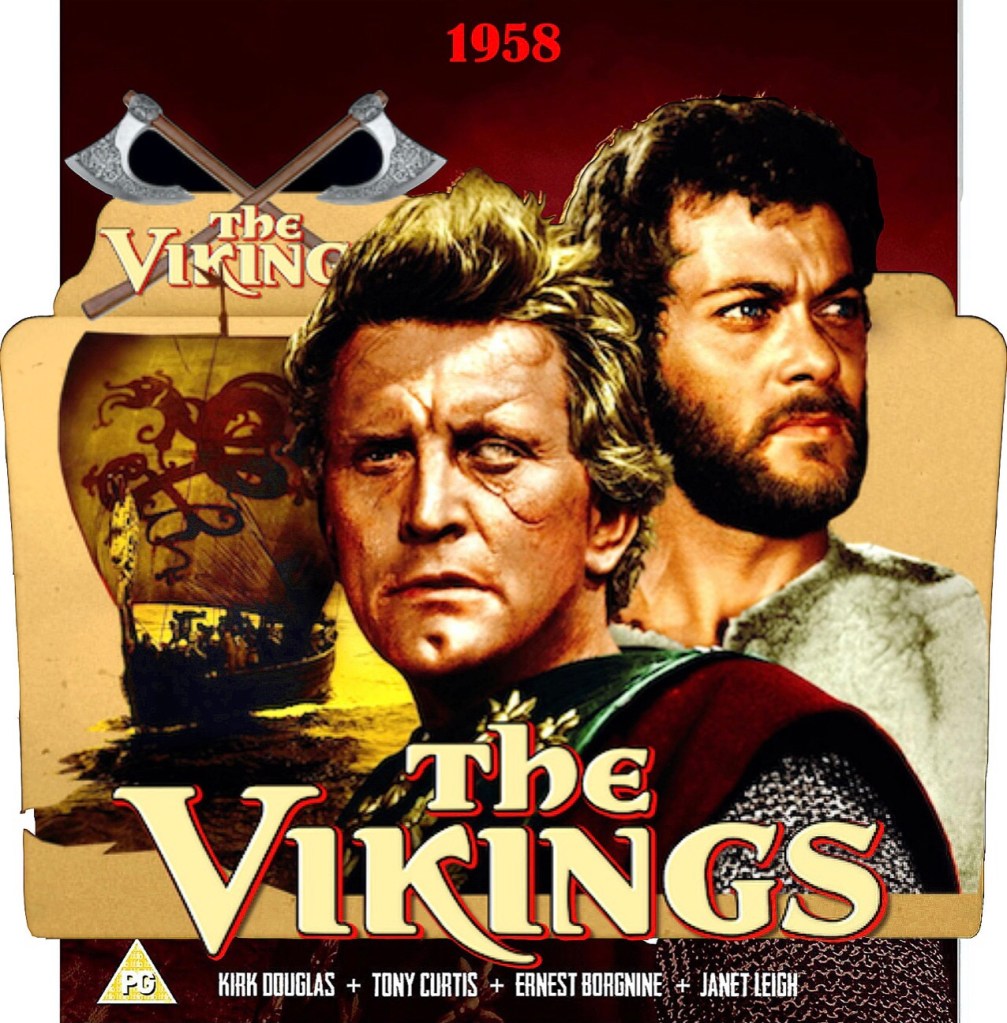

It turns out Leroy is teaching a class on West Point History. In his research for the class, he came across a book called “The West Point Sketchbook”, published in 1976. In the book, the authors state that in 1958, some cadets saw the movie “The Vikings”. It’s a so-so adventure movie, with an all-star cast of Kirk Douglas, Tony Curtis, Ernest Borgnine and Janet Leigh. Throughout the movie, The Vikings make various appeals and chants to Odin, including asking him to effect the weather and bring rain. In the movie, it worked. The cadets brought the Odin chant back to West Point, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Of course time and history evolve. Another classmate, Pete Eschbach was recently back at West Point and spoke with a few cadets about some of our past traditions. None of the current cadets had ever heard of appealing to Odin to cancel a parade. Not one. For the West Pointers reading this blog, Pete privately speculated to me that “Perhaps both The Corps, and Odin have… (gone to hell)”.* Maybe with the increases in technology, and the weather apps we have today, it’s no longer required. The weather is a foregone conclusion, and an appeal to Odin isn’t going to change things one way or another. Another mystery…

The legend of Odin may have died at West Point, but he remains an item of interest for me and my classmates. Occasionally, one of us still calls on him. Classmate Joe Mislinski even named his dog Odin. Joe lives pretty close to the Great Lakes Naval Station, where Navy basic training is conducted. He likes to occasionally take Odin for a walk outside the station, once a parade has already started. From the look of the slick streets in the photo below, Odin still has the occasional magic touch.

Addendum:

⁃ * Pete was making a bit of an inside joke to me about “Perhaps both The Corps, and Odin have… (gone to hell)”. In a tradition probably as old as West Point itself, among old grads you frequently hear the phrase, “The Corps Has…” Every class at West Point believes that the classes who came after them had it easier than they did. Gone to Hell is never stated, but always implied. 😉

⁃ Thanks to classmates Peter Eschbach and Leroy Hurt for their contributions to this blog, and their reviews. They were invaluable. Special Thanks to Joe Mislinksi for suggesting the idea for a blog about Odin, and providing a picture of his dog Odin!

⁃ In The West Point Sketch Book, it is reported that prior to 1958, Plebes would whistle a song called the “Missouri National” to try and bring on rain. Part of the adapted lyrics include: And now the rain drops patter down/ Our hearts fill with delight/ For hear the OD sounding off-/ “There is no parade tonight.”

⁃ The movie, The Vikings, is actually not bad. You might give it a watch sometime when you have nothing to do. In the meantime, here are several of the callouts to Odin, throughout the movie: https://youtu.be/uAM85DFfR24

If you wish to read a few of the previous blogs from my time at West Point, you can find them here:

- My First Two Hours at West Point: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2017/03/18/first-two-hours-at-west-point/

- Eating Potato Children: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2020/08/05/drunken-potato-children/

- Sir, The Days: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2018/02/09/the-days/

- Public Display of Affection: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2017/06/30/public-display-of-affection%EF%BB%BF/

- Gaining Nine Pounds in a Day: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2019/11/21/gaining-nine-pounds-in-a-day/

- Gloom Period: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2018/01/21/gloom-period/

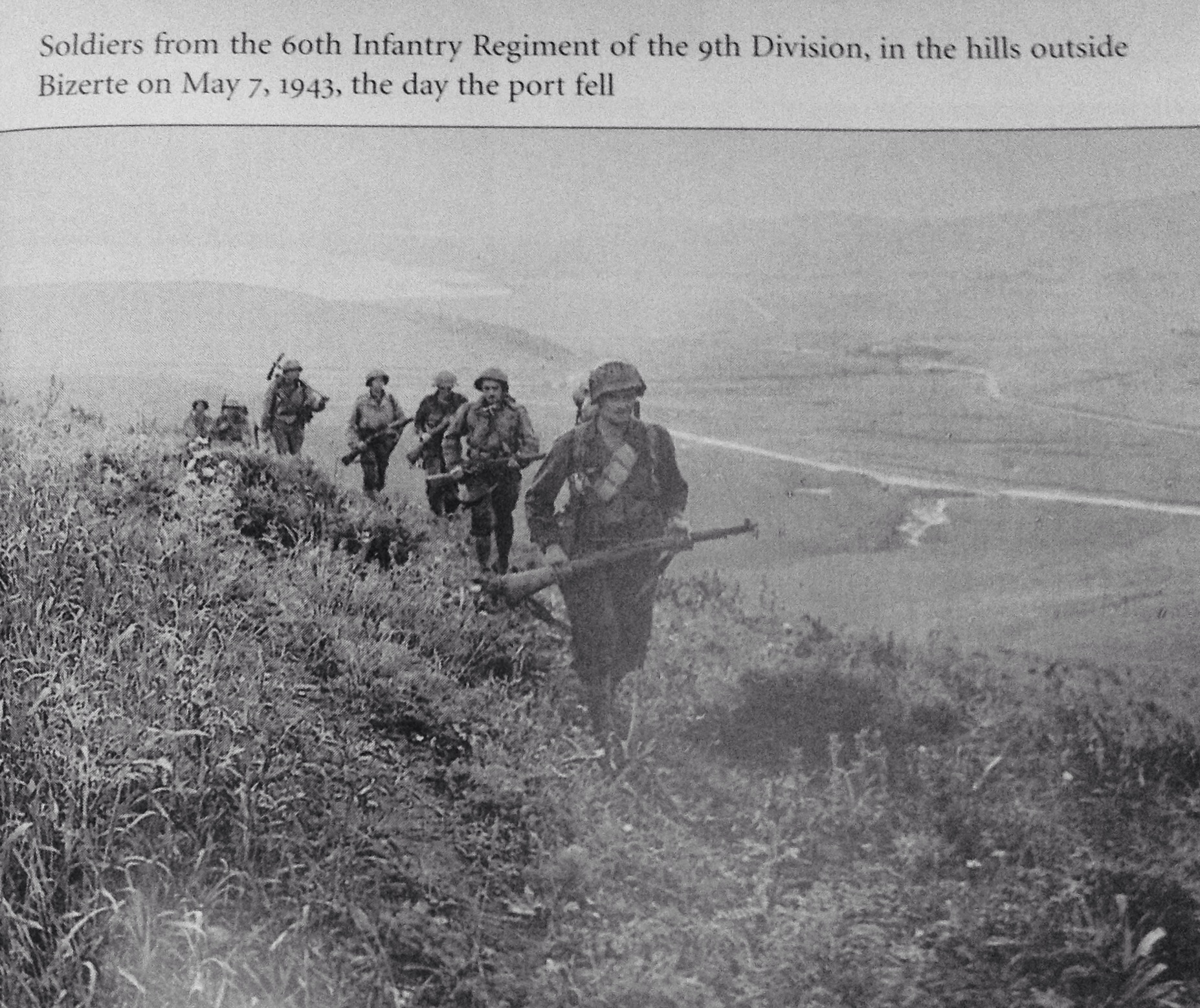

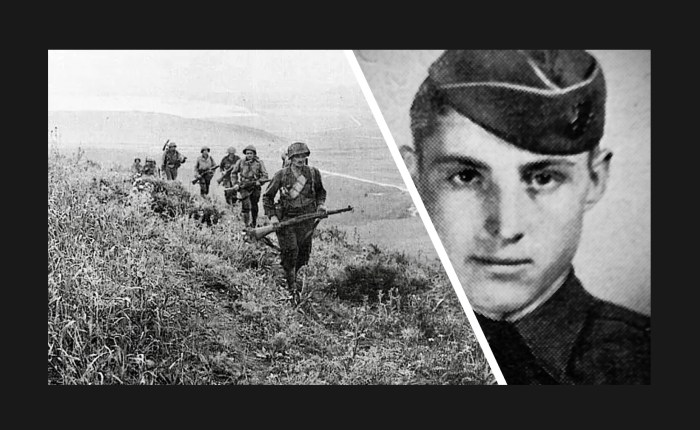

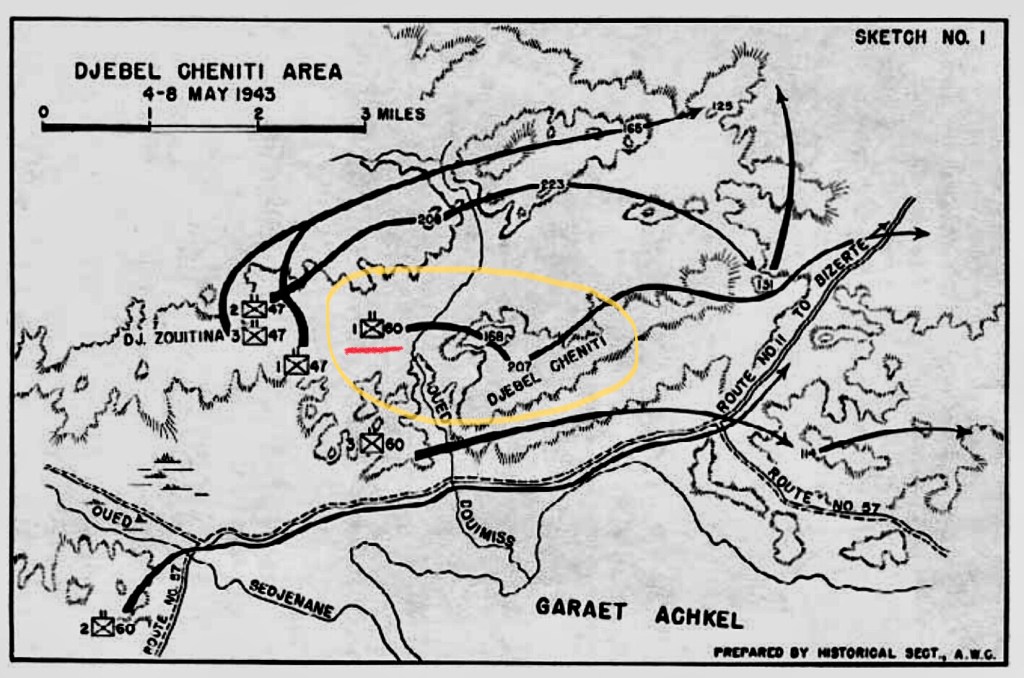

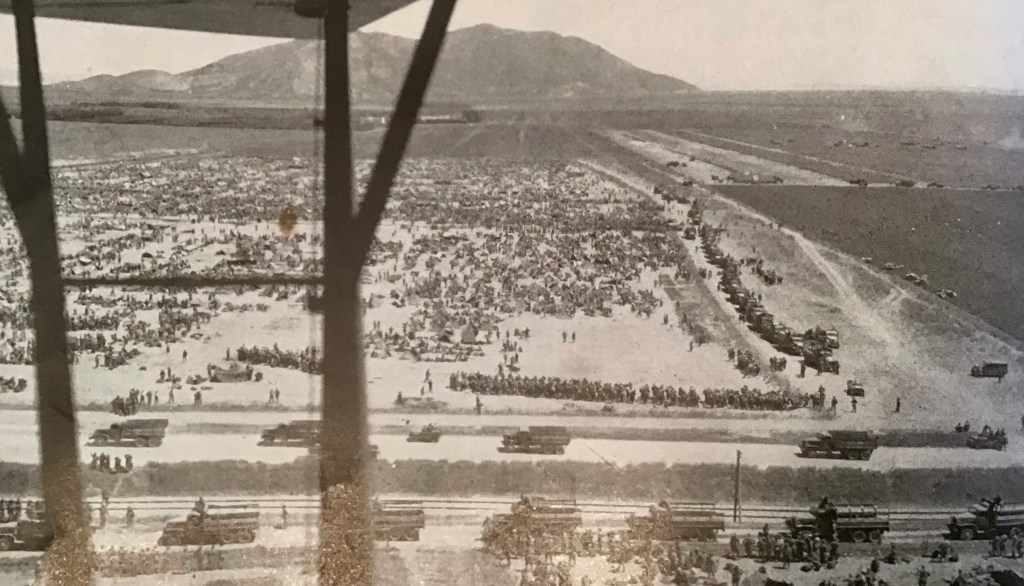

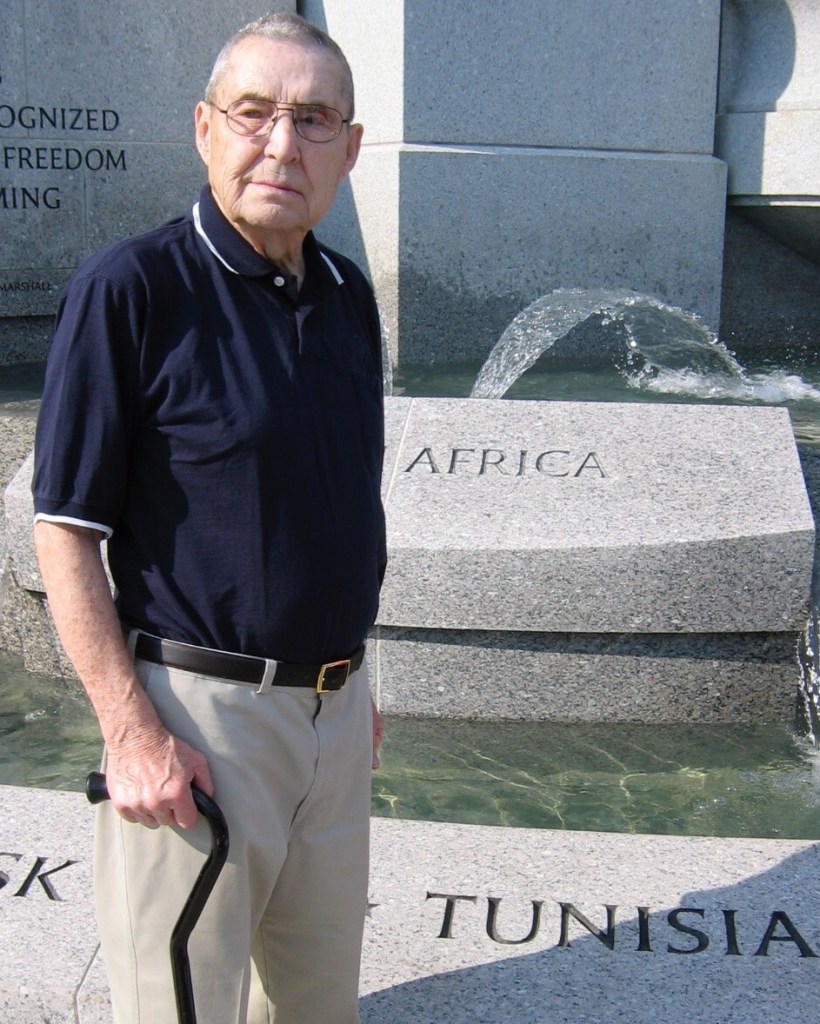

The 60th attacked a series of hills on the nights of the 22d and 23d with mixed success. As dad explained “we always attacked at night, but the Germans were well dug in. And they had mines on many of the approaches. The Germans used mines everywhere. The going was very slow.” They did take several of the hills, particularly on the north side of the pass, but the Germans still controlled the south side. Hill 322 was attacked many times but never taken. The advance bogged down, but the US Forces acted forcefully enough to cause the Germans to deploy reserve units, keeping them from engaging with Montgomery and the British, further to the south. Dad said that from where they were, they could actually see the open land on the other side of the pass, even though the Germans still controlled the south side of the pass. That open ground was what the tanks needed.

The 60th attacked a series of hills on the nights of the 22d and 23d with mixed success. As dad explained “we always attacked at night, but the Germans were well dug in. And they had mines on many of the approaches. The Germans used mines everywhere. The going was very slow.” They did take several of the hills, particularly on the north side of the pass, but the Germans still controlled the south side. Hill 322 was attacked many times but never taken. The advance bogged down, but the US Forces acted forcefully enough to cause the Germans to deploy reserve units, keeping them from engaging with Montgomery and the British, further to the south. Dad said that from where they were, they could actually see the open land on the other side of the pass, even though the Germans still controlled the south side of the pass. That open ground was what the tanks needed.