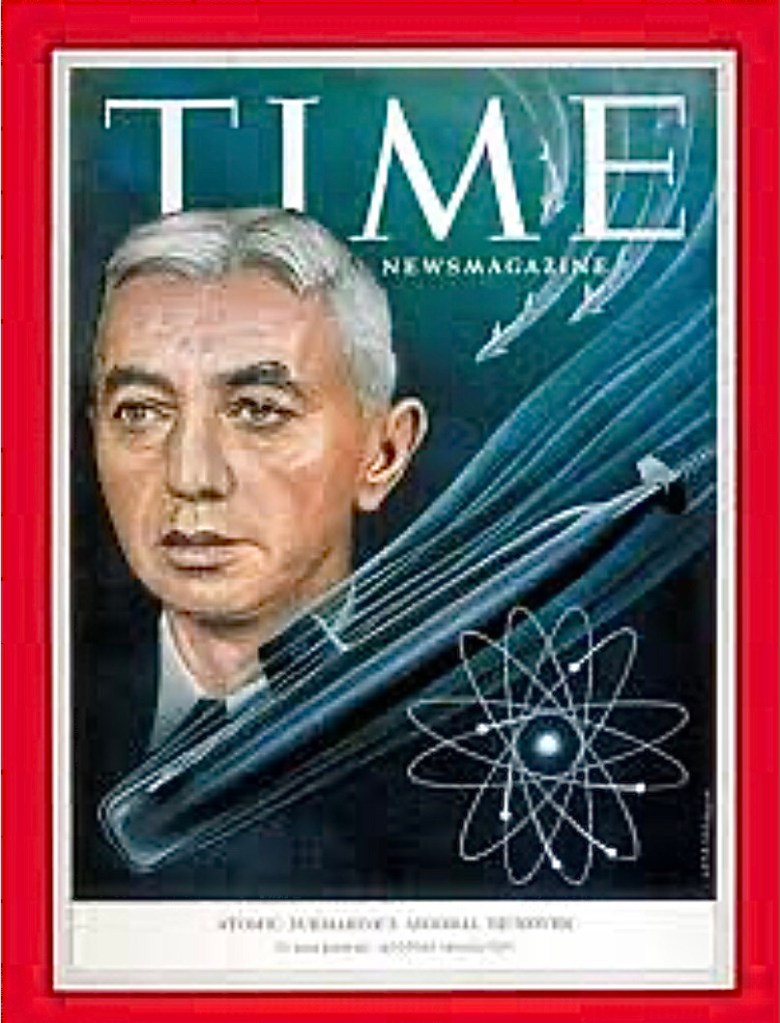

My friend Bob Bishop, straight out of the US Naval Academy, was interviewed by Admiral Hyman Rickover in 1964 for admission to the Navy’s Nuclear Power Program. Rickover, known as the “Father of the Nuclear Navy”, served in a flag (General Officer) rank for nearly 30 years (1953 to 1982), ending his career as a four-star admiral. His total of 63 years of active duty service make him the longest-serving naval officer, as well as the longest-serving member of the U.S armed forces, in history. In 1954, with the launch of the first nuclear submarine, the USS Nautilus, he appeared on the cover of Time Magazine.

There were those who loved him and those who hated him. He exercised tight control for three decades over the ships, technology, and personnel of the nuclear Navy. He interviewed every single prospective officer considered for service in a nuclear ship in the US Navy until his retirement in 1982 at the age of 82.

According to Wikipedia, “over the course of Rickover’s career, these personal interviews numbered in the tens of thousands; over 14,000 interviews were with recent college-graduates alone.” Many of those interviews are now lost to history. Here is the story of Bob’s interview in his own words.

***********

Much has been written regarding the harshness of his interviews, but none can criticize the results. Certainly none of those who successfully emerged from the crucible would do so.

On Friday, January 21, 1964, I was a First Classman (senior) at the Naval Academy and joined 34 other classmates on a bus to DC to be interviewed for the nuclear power program. At the time, many offices of the Navy were still located in “temporary buildings” built on the Mall during the Second World War – and were still in use twenty years later.

There were lots of tidbits floating around about the interviews with Admiral Rickover, aka “The Kindly Old Gentleman,” (abbreviated KOG), although never called that to his face. One such rumor was that the chair you sat in was rigged so it rocked if you were nervous. Most importantly, you should answer any question quickly and decisively.

Needless to say, I was apprehensive. We (there were also a couple of busloads of Midshipmen from Navy ROTC schools) were herded into a large semi-circular room with simple folding chairs, arranged in rows facing the center of the room. There were four passageways leading out from that central hub like spokes on a wheel. There were a couple of vending machines and we were told a head (bathroom) was just down one of the passageways. We were told not to talk to one another. We were also told to remain in the room until your name was called, and that was all. To be honest, we were afraid to even go to the head, because what happened if your name was called and you weren’t there? So, there we sat. Soon, someone would come down one of the hallways and call out a Midshipman’s name. He (there were no women at the Naval Academy for another 13 years) would rise and go with him, and sometime later come back and sit down. The scuttlebutt was that each person would have three interviews before potentially meeting with the Admiral, although some had four and a few had five. Some of those interviews were short (5-10 minutes) and some were long (an hour plus). Also, you had no idea if the person interviewing you was a chief petty officer, a prospective commanding officer, a member of the Nuclear Reactors division or somebody else – they were all in their 40s-50s and all in civilian clothes.

I had three interviews and what we discussed became a blur – I was so focused on answering the questions, I really couldn’t remember the questions even immediately after they were asked. I was thinking on how I did, was I sitting up straight enough, remembering to be decisive, etc. The one question I remember most clearly was being asked about the window air-conditioning unit. I started into a description of the freon cycle when I was stopped. The questioner wanted to know why it didn’t fall out of the window. I started postulating about ways it could have been installed so it wouldn’t fall either in or out. I also remember being asked the value of studying naval history (pro and con), why I decided to go to the Naval Academy, what was Bernoulli’s equation, and why did I want to go into nuclear submarines.

Each time I went back into the central room, there were more and more empty seats. With no one to ask, I merely presumed they had finished the process. I worried and wondered if it was good news or bad that I was still there. As I sat there, morning became afternoon and afternoon night. Eventually, there were maybe three or four of us left. It was 8 something PM, and my name was called. I was led down a narrow corridor, lit only by bare light bulbs hanging down periodically the length of the corridor and into the distance. Light showed in the hallway from only one office, at the end of the corridor on the right. As we approached, my escort told me the Admiral’s yeoman (Navy admin) was gone and I should just walk past her desk and into the Admiral’s office and sit down in the empty seat.

I did and sat down in the Navy issue aluminum square channel chair, with a naugahyde seat. The room was a little dark. The scuttlebutt was right – the two front legs were shorter than the back legs, and one of the front legs was shorter than the other so that, if you were the least bit nervous, you would slide off the seat or rock sideways. I sat with my butt firmly implanted up to the back of the chair, giving thanks to the many hours I spent plebe year on “The Green Bench” (envision sitting in a chair against a wall, with your knees/lower legs at a 90° angle and your thighs/lower back also at a 90° angle – now take the chair away).

His office was a mess. It was about 10’ wide and 15’ deep. There was a bookcase behind me, another on the wall to my left, bookcases down each wall, and a big old wooden desk directly ahead. Each of the horizontal surfaces, including his desk, were piled high with a hodgepodge of varying heights of stacks of books, interspersed with folders. The door I came in was on my right, behind me. I was focused straight ahead (the Navy term was “keeping your eyes in the boat”), but my peripheral vision, and attention, was focused to my right so I could immediately rise as soon as he came in.

Three or four minutes passed when all of a sudden, I heard a loud voice say, “Why the f**k have you been wasting all your goddam time?” I immediately focused straight ahead and there he was, and had been the whole time, obviously just watching me. I never met an Admiral before and certainly never expected one to curse. Notwithstanding the advice to respond quickly and cogently, what do you suppose came out of my mouth? “Umm, er. . .” “What?!” he said. “I have been working hard, sir.” “Don’t give me that shit,” he replied. Our “discussion” did not go much better, although I don’t remember much of it, just the feeling it was going a lot less than well.

Things I remember vividly – At one point, I said something along the lines of “I think there is more to education than just book-learning.” Big mistake. Unfortunately, not the last. Our discussion circled back around to my grades (I thought afterwards he must have those in a folder on his desk). He asked what my class standing was going to be when I graduated. I knew I was doing pretty well but I had no idea what the current number was, so I said “55.” He replied, loudly, “WHAT?” I said “50?” a little plaintively. He said, “DO YOU MEAN . . . ?“ I quickly interrupted and said “45?” He roared “GET THE F**K OUT OF MY OFFICE!”, which I rapidly did.

What felt like a three-hour-long crucible under intense heat, actually lasted around twenty-two minutes. It took me a couple of hours, and a couple of scotches, to get my resting heart rate down. I also started thinking of what I wanted to do in the Navy, other than nuclear submarines, when I graduated. Plainly, I wasn’t going to be selected.

A couple of months later, a list was posted at each of the twenty-four company offices at the Academy. The word quickly spread so each of us Firsties (seniors) who had applied hurried down the corridor. If your name was on the list, you were in. I read the list, haltingly, three times to make sure that was really my name.

Postscript – I had three other interactions with the KOG during my six-plus year career in nuclear submarines. Not bad for a mere lieutenant, but those are stories for another time.

Addendum:

- if you have the time, it’s worth reading up on Admiral Rickover’s career. It was pretty amazing, although he actually only commanded one ship. Some of his detractors compared his hold on the Navy, and particularly the Nuclear Navy, to Hoover’s hold on the FBI for all of those decades. He was a brilliant man, and there’s no doubt our Nuclear Navy would not be where it is without him.

- Bob is a wonderful storyteller. Here are two other blogs from his time in the Navy on a Nuclear Submarine:

- The movie, “The Hunt for Red October” is child’s play, compared to what these submariners did on a daily basis … “The Comms Officer ran in and handed the CO the decoded message. The CO read the message, took the lanyard from his neck, unlocked the firing key cabinet, and reached in for the firing key. We were about to” […] Continue at: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2021/06/23/we-knew-we-were-at-war/

- Crazy Ivan anyone? … In 1970, our sub, the USS Finback, was helping with Anti-Submarine Warfare training for NATO aircraft. An observer on the sub said “I think I understand your plan. You alternate going to port or starboard as soon as you submerge.” I responded, “Well, not actually”, and we walked over to […]. Continue at: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2022/04/13/submarine-games