Colonel Bayshore called me into his office. “Max we have a problem at the new Alternate Support Headquarters (ASH) in England and need you on a plane.” “What’s the problem?” “A grounding issue.” “Ummm, I don’t know anything about grounding.” “None of us do. Here’s the manual.”

In 1988 Cath and I were stationed in Germany with the Information Systems Engineering Command (ISEC). I was a Captain at the time and had my master’s in electrical engineering. ISEC did all kinds of complex Information Technology (IT) implementations.

When Colonel Bayshore called me into his office to talk about the ASH*, it was a classified site. The US European Command (EUCOM) ASH was in High Wycombe, England and where EUCOM HQ would bug out, if they needed to evacuate Germany during a war. Originally built in 1942 during WWII for other reasons, the US government later rebuilt the bunker to support the ASH during the Cold War. It was an underground complex and built to survive not only conventional bombings, but even an ElectroMagnetic Pulse (EMP) nuclear attack.

The site wasn’t yet occupied. The system installations were handled by a different organization than ours, with much of the IT work completed by a contractor. Most work was completed with systems installed, but one of the classified rooms had a problem. Whenever you used the secure phones in the room, there was crosstalk with other phones, making it impossible to have a classified conversation. The ASH facility could not pass its security accreditation until the issue was resolved. This meant the faculty could not undergo final testing or become operational. An engineer “somewhere” thought it was a grounding problem. They contacted ISEC for outside support, resulting in Colonel Bayshore’s call to me.

Sergeant First Class (SFC) George Walls would also go on the trip. George was great and a super technician. We would work as a team at the ASH until we solved the problem.

The next day, George and I started reading “MIL-HDBK-419A – Grounding, Bonding, and Shielding for Electronic Equipments and Facilities Volume 2 of 2” (Volume 1 was theory. Volume 2 was applications). At 394 pages, it was a massive document and told us everything and anything we could possibly want to know about grounding buildings and electrical systems within those buildings

A day later, we were on a plane crossing the Channel. We continued reading and rereading MIL-HDBK-419A.

Arriving in England at the ASH, we met our government point of contact (POC) and a representative from the contractor. They were skeptical we would find anything, but welcomed our help. Our job was to identify issues, but not to fix them. The contractor would complete the corrections, once tasked by the government.

After giving us a tour of the facility, they offered to accompany us as we started our work. We politely declined, and let them know if we needed any help, we would contact them. We didn’t want anyone looking over our shoulders – partly to minimize outside interference in our investigation, and partly so no one could see how green we were in our knowledge of grounding. Quoting from the book/movie “MASH”, we were “The pros from Dover”** and we didn’t want anyone questioning that.

We started our work in the classified room with the crosstalk problem and spent two days checking every system, circuit, wall plate, ground connection and the entire ground grid underneath the raised floor in the room. We found some wall plates that weren’t grounded and one improperly grounded system, but found no issues related to the crosstalk problem.

From there, we proceeded to the classified phone switch room and did the same type of inspection. Again, we discovered several issues, but none that we believed caused the crosstalk. We hadn’t solved the problem, but our list of grounding issues within the facility continued growing.

Next, we went to the Tech Control Facility (TCF) where all connectivity (cables, wires and radio channels) for the systems going into or out of the ASH passed through. We documented more and different grounding issues.

With the growing list of problems, I called COL Bayshore and recommended we inspect the entire underground facility for grounding issues, including all rooms, systems and connections. This was outside our original scope, but both George and I were concerned with what we were finding. COL Bayshore agreed, but needed approval for the expanded work. The next day, the powers-that-be gave approval.

We spent the next few weeks at the ASH continually documenting grounding issues. Many were minor, but some were major. As one example, in a room housing the Worldwide Military Command and Control System (WWMCCS), all systems were properly connected to the ground grid below the raised floor, but the ground grid itself was not connected external to the room, making it worthless. In another case, the grounding cable for an external backup generator was almost cut in half. At some point in the past, the generator startup battery arced to the ground cable, nearly severing it.

After about three weeks, we finished our inspection. Our list of grounding issues was twenty or thirty pages long and many items needed correction prior to the facility going operational. We sent a copy back to our headquarters at ISEC and also gave a copy to the facility government POC. Needless to say, with the number of identified problems, there was a bit of shock both back at our unit, and in the facility.

Unfortunately, we still hadn’t solved the crosstalk issue.

That night as George and I were having dinner and a beer, we talked things over. We tossed some ideas back and forth, and ultimately decided we would track a single phone circuit in the classified room from the phone to the connection plate to the classified switch to the TCF and see if we could find the problem. Maybe it wasn’t a grounding issue.

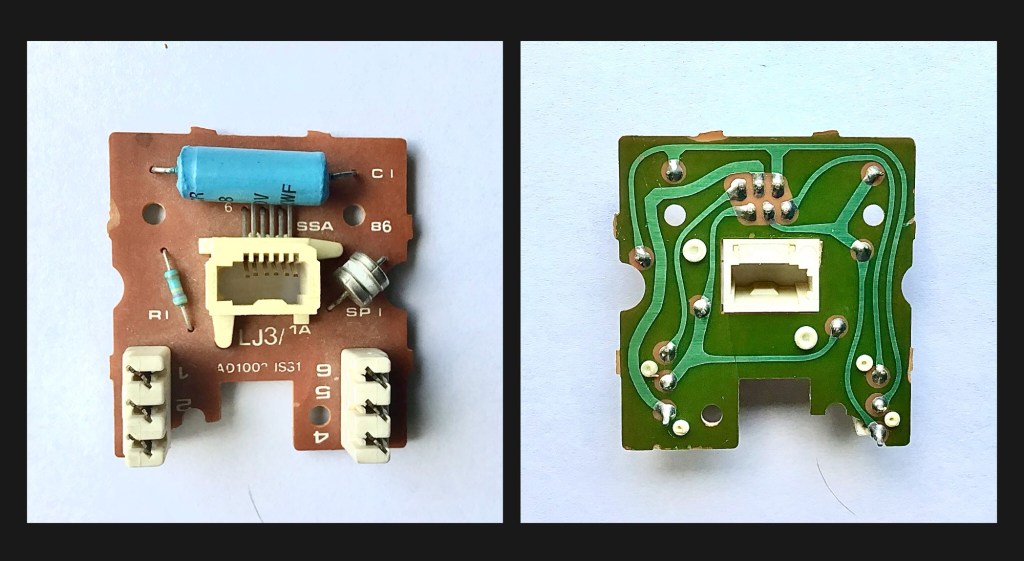

The next day, we were back in the classified room and pulled one of the phones from its cable and inspected it. Nothing…Nada…Nope. From there we traced the phone cable to the wall plate. We took apart the wall plate and pulled out the physical jack the phone plugged into. As we looked at one side we noted the connection port, a resistor, and a couple of capacitors – nothing too exciting there. We turned it over and started tracing the circuitry. HELLO! What’s this? Two capacitors were interconnected and double connected to different circuit posts in the jack where the phone itself connected.

We stared at the wiring and started talking. Was this the issue? There was only one way to find out. George pulled out a pair of wire cutters and …snip snip… cut the connections for the suspected capacitor.

We reassembled everything, plugged the phone in and made a call. NO CROSSTALK!

We notified COL Bayshore and then spoke with the POC and the contractor about what we found. They were shocked (and surprised we had the temerity to cut the connections). We eventually tracked down why the connectors were incorrectly wired. It turns out the phones all came from the US for the classified system. The contractor obtained the connectors in Europe. They may have worked with the European equivalent phone, but they would not work with the US version as wired.

George and I were still in England for the next couple of days and had become minor celebrities of sorts. Calls came in from both DC and Fort Huachuca, Az where they completed the original system implementation/design work. The calls were a bit funny. People congratulated us, but couldn’t quite believe we solved the problem, or how we solved it. They asked several questions – some we could answer, some we couldn’t. It didn’t really matter to George or me by then. We’d finished something no one else had solved, mostly through detailed work, and a little bit of luck.

A couple of days later we made our way home to Germany, mission accomplished.

I have thought about the trip more than a few times since then. Becoming an “instant expert” was important. I knew I wasn’t really an expert at the start, but I knew we had more knowledge about grounding than anyone else connected to the program. By the time we finished, we truly were grounding experts.

Finding the many grounding problems was important. The issues probably would have gone unnoticed until a system failed, possibly during a real-world crisis.

Lastly, it was important to remember that sometimes the problem isn’t what you think it is, or what others think it is. Sometimes it’s something so small and innocuous it goes unnoticed, just sitting there looking innocent. Keeping an open mind is always important.

Addendum:

- * The EUCOM ASH Bunker – The bunker was built in 1942 during WWII. In the 1980s, it received a major upgrade and was a designated alternate HQ for EUCOM, should forces in Europe be overrun. You can read a bit more about the site here. https://www.bucksfreepress.co.uk/news/13486789.wycombe-abbey-school-opens-former-wwii-and-cold-war-bunker-for-one-visit/ – note the photo of the descent into the bunker is from this article.

- ** Here’s a link to the movie “Mash”, and the famous “Pros from Dover” scene: https://youtu.be/KojghwX_9eM?si=m2qHzQy_CkDswCvI