It is one of my favorite photos from our time in the Army. I say “our time” because that is what it was. I was the soldier, but Cath and I were both a part of Army Life. To me, the picture brings back the memories of the great joys, along with the intensity of everything in the Army of the early ‘80s.

Continue reading “Army Times”Tag: #Coldwar

Returning Home from Germany

In June of ‘83, I returned to America after serving 4 1/2 years with the Army in Germany. At the time, the Post-Vietnam dislike of soldiers was still alive, a decade after the war. Returning to the States, I had a good experience at the airport that still gives me shivers today.

It’s different now and we as a country, or at least most of us, have learned to separate politics from the people serving in uniform. Back then? Post-Vietnam? We weren’t so great about how we treated our soldiers. I remember someone spitting at me as a cadet while walking in New York City in the mid-‘70s. In 1979, right before we first deployed to Germany, a woman from our church commented to my mom about how terrible it was that they as taxpayers had to pay for Cathy to go to Germany with me, and for us to be able to take some of our belongings with us. AND this was a woman from our church I’d know since I was a child.

Of course most family friends, and our close friends were great with us, but past that? Things were often ambiguous. None of this was as bad as soldiers put up with during Vietnam, but it would be years later before we (as a country) really learned to separate politics and our respect for our soldiers.

In June of ‘83, I turned over my Company Command in Stuttgart, Germany. I had a couple of weeks of additional work I needed to do, so Cathy flew back ahead of me. Finally it was time for me to go home and I flew on a commercial flight wearing civies. We landed at Dulles and I made my way to customs where the line seemed about a mile long. Several flights arrived at the same time, and the line wasn’t moving.

As I stood there, I noticed a young lady walking down the line looking at people in the line. Eventually she arrived in front of me and said “Are you in the Armed Forces?” I’m sure my short haircut and bearing probably gave me away.

I answered “Yes ma’am, the Army.” and she said “Follow me.”

I walked with her for quite awhile and we finally arrived at the front of the customs line. One of the stations opened up and she walked me over to it. The guy behind the counter looked at me and asked for my passport, or my military ID and orders, which I produced for him. He took a quick look, handed my papers back to me and then said, “Thank you for your service. Welcome home to the United States of America.”

I still get a shiver typing those words today. It was the first time someone went out of their way to thank me for what I was doing, and then welcomed me home to boot. It was such a little thing, but plainly had a huge impact on me. I remember it clear as a bell forty years later.

I’ve thought about this story lately. Probably since Panama in ‘89, and certainly since the First Gulf War, we’ve thanked our soldiers and shown respect for them. Unfortunately, an annual poll conducted last November by the Reagan Institute shows respect for the military dropping from 70% in 2017 to 48% in 2022. Much of the drop was attributed to people (from both sides) trying to politicize the military, or what the military was doing.

To be quite frank, most people today have no connection with our armed forces. Their sons and daughters aren’t in our military. If fact, over 70% of American youth today aren’t qualified for the military. They are overweight, or are doing illegal drugs, or are doing legal drugs that make them ineligible for military service. I fear that for many, saying thank-you is a cheap and easy way to feel good, while not really caring about our troops. Maybe I have that wrong, but I’m not so sure.

As time progresses, I’m hoping we as a nation can adult enough to remember to mentally separate politics and the soldiers serving in the military. I hope that we can take a couple of minutes to genuinely thank our troops. Not pro forma, but really thank them. We continue to owe them that much.

Addendum:

- in a side note, in the 4 1/2 years we were gone on that tour, I only made it back to the States once. That was to attend my sister Tanya’s wedding. When Roberta married the next year, we couldn’t afford another trip home. It was one of the many family events we would miss over the course of our almost 9 years overseas.

- Thanks to my wife Cathy for input to parts of this blog. As an Army wife, she too remembers those days. Like me, she is also concerned about the lack of connectivity between our society and our military today.

Submarine Games

Crazy Ivan* anyone? Another Submarine story from my buddy, Bob Bishop**… It was mid-September, 1970. Our submarine, the USS Finback, had been commissioned way back in February, but we were still doing a number of exercises and independent operations to get additional sea time under our belt. On this particular exercise, we were to provide “services” to anti-submarine warfare (ASW) configured Navy patrol aircraft, to give them an idea of how to use their ASW gear and try to find a real live nuclear submarine. This exercise was to involve every ASW patrol plane on the US east coast, NATO members in western Europe, and one reserve squadron from Chicago (don’t ask me why there is an ASW squadron in Chicago).

In the Atlantic Ocean, that meant a complex organizational challenge for a lot of people. For each exercise, using radar and radio communications, we would vector a Navy Lockheed P-2 Neptune or P-3 Orion aircraft on top of our location so they could mark where we were. We would then submerge and maneuver. If they didn’t find us in 50 minutes (marking our location by dropping a transmitting sonar buoy), we would broach or surface, show them where we were, and they would then clear the area for the next plane to arrive at the top of the hour. We did this for 18-20 hours a day most days, for 4½ weeks.

During the exercise, we also did occasional helo transfers of a CO/XO from an aircraft squadron to our ship, so they could get a sense of what it was like to be on a submarine and how we operated during these exercises. I particularly remember one squadron XO, a Commander (I was a lowly Lieutenant, but was pretty comfortable with what I knew and no longer frightened by a senior officer), who came in the Control Room after midnight one night. I was the Officer of the Deck (OOD) – the officer on duty responsible for driving the ship, responding to emergencies and so on, unless the Commanding Officer came on deck to relieve me. I had the 0000 to 0600 watch and we were in the middle of conducting the ASW exercises.

We talked over a number of things he was curious about, and he watched as I/we went through a couple of the exercise cycles. Chatting after the third one, he observed “I think I understand your plan. You alternate going to port or starboard as soon as you submerge.” I responded, “Well, not actually”, and we walked over to the chart table. A piece of paper was taped on top of the glass top of the chart table. A mechanical device under the glass receives inputs of the ship’s speed and direction and moves a little light accordingly. Every minute the quartermaster puts a pencil dot where the “bug” (the light) was. As a result, you could see where the ship had been.

I quickly explained how “the bug” worked and showed him where we started the last run and where we ended up 50 minutes later. I then explained that the Captain gave the OOD the latitude to do whatever he wanted, so I decided to spell the Helmsman’s (the person actually steering the ship) name in cursive each watch. I think the letter I was on for that particular run was a “b.” The Lt Commander looked at me, aghast. “You mean, you don’t have a pattern, a routine?” “Nope,” I said, “It all depends on when I am on watch and who the Helmsman is. Although sometimes I use the name of the Stern Planesman or the Diving Officer.”

He walked quietly away, mumbling to himself.

During the 4 1/2 weeks of the exercise, not a single plane ever found us, even though they knew where we started each time. A discussion about the capabilities of ASW aircraft is a subject for another day, but I’ll leave it at this – ASW aircraft (including helicopters) vs. a US Navy nuclear submarine? Bet on the submarine, every time.

Addendum:

– * Crazy Ivan references a maneuver sometimes performed by Russian submarines, and made famous in the movie. The Hunt For Red October.

⁃ ** My friend Bob Bishop graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1964 and had several tours on Nuclear Submarines during the Cold War. At the time, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the founder of the modern nuclear Navy, personally interviewed and approved or denied every prospective officer being considered for a nuclear ship. The selection rate was not very high.

– This story is pretty much all Bob’s. All I did was add some editing assistance and publish it.

⁃ The USS Finback (SSN-670) was a nuclear-powered fast attack submarine. Bob was a “plankowner” – a member of the initial crew. He was the third officer to report on board.

⁃ You can read another of Bob’s submarine adventures here. It’s a compelling Cold War story. The movie, The Hunt for Red October, is child’s play, compared to what these sailors did on a daily basis. …The Comms Officer ran in and handed the CO the decoded message. The CO read the message, took the lanyard from his neck, unlocked the firing key cabinet, and reached in for the firing key. We were about to […] Continue at: https://mnhallblog.wordpress.com/2021/06/23/we-knew-we-were-at-war/

Lariat Advance

The call came at about 3:40AM in late February, 1979. I answered the phone, “LT Hall.” – “Max, this is Captain Ward. A Lariat Advance Alert was called at 3:25AM this morning.” – “Got it sir – on my way.” I called my Platoon Sergeant, Paul Teague to notify him, and kissed Cathy goodbye, with a “See you when I can”. I was out the door for the drive to Hindenburg Kaserne by 3:50AM.

We lived in the little town of Helmstadt, Germany, about 15 minutes from Hindenburg Kaserne (Barracks, or Army Post) in Würzburg. My mind raced on the drive to the barracks.

This was my first Lariat Advance. I’d joined the 123D Signal Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division in January of ‘79. A Lariat Advance was a US Armed Forces Cold War mobilization alert in Germany. The thing was, you never knew if it was a drill, or in response to a real world situation. If just a practice, it might be called off after a couple of hours. BUT, you could also deploy and link up with the unit you supported (2nd Brigade, 3ID in my case), or even deploy to your General Defense Plan (GDP) location. For my platoon, that was near the village of Hof, and the Hof Gap on the the Czech/East German border. The Hof Gap was considered a major Armor Route for a Russian invasion of West Germany. The pucker factor increased significantly if you deployed there on an alert.

My unit, B Company, 2nd Platoon, was always the first unit scheduled for departure, as we had farther to go. We would depart two hours after the alert was originally called. In this case, we needed to be lined up at the Kaserne Gate and ready to go at 5:25AM.

I arrived at the Kaserne a few minutes after 4:00AM. As I climbed out of the car, I promptly locked my keys in the car. “D@mn!” I stood looking at the car, shaking the door when one of my squad leaders, Sergeant Santos ran by and called out – “Yo, L.T. (Pronounced Ell-Tee), what’s up?” – “I locked my keys in the car.” He stopped, looked at me for a second and then said, “Forget ‘em. We’ll get them later – we gotta go!”

He was right, of course. I left the car and ran to the Company HQ and checked in with the CO. Next, over to the Armorer, where I picked up my .45 pistol, and finally, I ran back outside and over to our Platoon Bay. It was probably about 4:15AM.

Sergeant Teague had also just arrived and he gave me a status report. About 80% of our troops were on the Kaserne, with the others expected shortly. We then looked at our vehicles’ status. Our platoon had around 20 vehicles in all – a combination of jeeps, a 2 1/2 Ton truck (the Deuce) and several Gamma Goats. Gamma Goats were six wheeled vehicles that could, at least in theory, perform off road much like a tank, or other tracked vehicle. We needed to determine which deadlined vehicles could be made readily available, by cannibalizing* other deadlined vehicles. We agreed that of our four deadlined Gamma Goats we could maybe get three ready, and still make the 5:25 departure time.

The next half hour was total chaos. By then, all of our troops but one were on the Kaserne and had picked up their weapons. We continued loading both personal and platoon equipment into our vehicles. Cases of C-rations were loaded into the Deuce, along with other supplies. Two of the deadlined vehicles were fixed, but we were still having problems with the third. Somewhere in there, we received word we would deploy to Kitzingen, and link up with 2nd Brigade’s HQ elements. It was now 4:55AM, a half hour before departure.

Suddenly, a feeling of great calm and clarity settled over me. The world seemingly slowed down. Sergeant Teague and I agreed it was too late to fix the last vehicle and to hell with it, we would roll with what we had. We held a quick meeting with our three section leaders and strip maps to Kitzingen were passed out for each of the vehicles (remember this was all pre cellphones or google maps). We lined up the vehicles in the motor pool and proceeded to the gate, with my Jeep in the lead. Sergeant Teague was in the last Jeep at the end of the convoy. At 5:15, we were at the gate where the Battalion Commander, Colonel Swedish and Command Sergeant Major Johnson greeted us. We spoke briefly and they wished us good luck.

5:25AM came, and we rolled. The rest of the day passed in a bit of a blur. Google maps says the drive from Würzburg to Kitzingen takes a half hour, but at convoy speed, it probably took us about an hour. We arrived and I reported in to the 2nd Brigade Operations Officer (S3). Then, as is often true in the Army, we sat and waited. And waited. I stayed in touch with the Brigade S3, and also with my Company Commander via FM radio. After a couple of hours passed, we received word it was a drill, and perhaps another two hours later, we were released and returned to Hindenburg Kaserne.

The drive back took another hour. Once back at Hindenburg, we offloaded all of our equipment, washed our vehicles, and then topped all of them off with fuel, so they were ready to go. Cannibalized parts were returned to their original vehicles. A weapons count was done by the armorer, and it was verified all weapons were turned in and accounted for.

I reported to Company Headquarters that all recovery tasks were completed. Once all three platoons were finished, Captain Ward let me know we could dismiss the troops, which I did.

By now, it was late afternoon or early evening, and my keys were still locked in the car. I started thinking about how I was going to get home, when Sergeant Santos came up. “Hey L.T. Let’s get those keys.” – “Sure, how are going to do that?” Ramos just smiled, and then pulled a Slim Jim** out of his jacket. Two minutes later, the door was open, and I had my keys. I thanked him, and decided right then and there, I didn’t need to know why he owned a Slim Jim.

With Russia and the Ukraine in the news, I was thinking about that first Lariat Advance. Forty years ago, we were concerned about, and prepping for war with, the USSR. After The Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the Cold War ended, I thought those days were behind us, at least for Europe. With Mr. Putin’s current aggression, that no longer seems the case. I’ve been thinking about an Intelligence flyer that came out, right after The Wall fell, warning us about the long term goals of the Russians:

It is no longer Communism against capitalism, but it is still Russia versus the West. Sometimes the more things change, the more they stay the same. I’m wishing Godspeed and safety to all of our troops.

Addendum:

• Cannibalize – If a vehicle was determined to have a safety issue, or something major wrong with it during operations or an inspection, it was put on the deadline report and the appropriate parts were ordered. You were not allowed to drive deadlined vehicles, until they were repaired. In the event of an alert, you “Cannibalized” one of the vehicles to remove parts to put in the remaining vehicles. It might be something as simple as a brake signal bulb (safety feature), or something more serious like a transmission problem. Cannibalization was frowned upon, as you could literally reduce one of your vehicles to a pile of parts in order to fix other vehicles. That one vehicle would stay on deadline forever. This is why we were to return cannibalized parts to the original vehicle when we returned to the Kaserne.

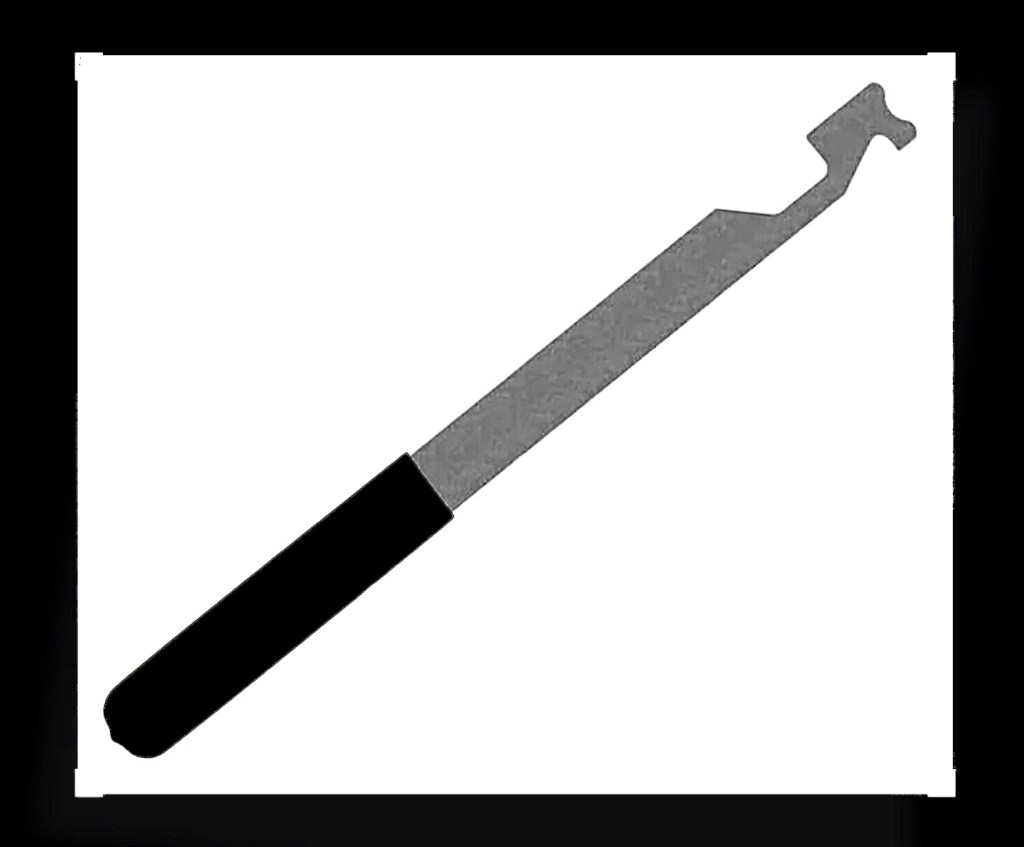

• **Slim Jim – For those unaware, a Slim Jim is a slender device used to break into a car by fishing down the side of window and into the door for the locking mechanism.